By Arthur H. Gunther III

Much progress in humanity, though it is often one step ahead, two back, comes from symbolism, such as the iconic nature of photographs that pull at our conscience and tell us, “We must do better.” For decades now, the mostly black and white work of Dorothea Lange, the famed social documentary photographer of the Great Depression, has been such a tug. And rightly so, for Lange, employed by the Farm Security Administration but also shooting from her soul, was gifted in capturing candid and semi-posed expressions of many trails of tears, suffering, endurance, just plain grit, survival and resurrection in that economic debacle. Yet, her work, like that of any reporter of an age, must always be subject to re-interpretation, not only to dispel myth but to add to fact, to the constant, deeper understanding that betters humanity.

Recently, I was introduced to the works of three people, one a British graphics designer/photographer who has reset Lange’s images as color true to the age, and a sister team that wrote and photographed in similar fashion during the Depression.

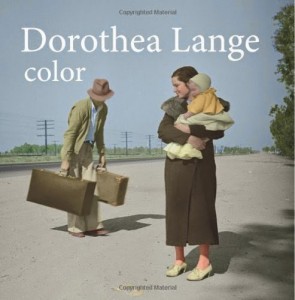

Neil Scott-Petrie from Cambridgeshire has produced an amazing tribute to Lange, and even more so, her social realism subjects, 1935-1939, by taking Lange’s black and white photographs and deftly and intricately adding accurate color. In doing so, he has brought realism to realism, and the viewer sees these iconic images of the huge ex-farmer migration from Oklahoma to California as if they were taken today.

Previously, when we looked at Lange’s work, while we focused with empathy on the hungry, perhaps “lost” children and distracted adults in search of work, trying to survive in a great calamity, we also saw their period clothes, the Model Ts, filling station signs, etc. That caused us to set the age apart, apart from reality other than that moment. We saw the images almost as fine art pieces, set for a museum installation. But with Scott-Petrie’s reworking of Lange’s shots, we view another time in humanity’s long struggle relative to today. And that is much to the good.

As the author notes, “This book is not about improving Dorothea Lange’s work, her images are amazing and cannot be improved. This is about showing her work in a different light, in color, bringing the real events closer to the observer, giving you a more realistic view of how things were during the migration to California … (after all) the world was not black and white.”

Indeed. I would urge Scott-Petrie to seek wider viewing of his added perspective of Dorothea Lange’s defining reportage, perhaps in a national gallery installation in London or New York. They would be a sure hit and would add to the story of humanity in struggle, a continuing novel that sees chapters even today in the worsening immigration problem in the United States.

(Neil Scott-Petrie’s “Dorothea Lange, color, The Migrant Experience 1935-39” may be accessed via dorothealange.com).

Lange was not the only social documentary reporter of the Great Depression. Also there were the Babb sisters, Sanora, a writer, and Dorothy, a photographer. Joanne Dearcopp, a longtime friend of Sanora, reminds me that Dorothy photographed migrant camps in the late 1930s and her sister wrote the novel, “Whose Names are Unknown.” Therein lie many stories. Sanora helped establish the FSA government camps for migrant workers in California, and her Dust Bowl refugee novel began there. Apparently, Random House was planning to publish this “exceptionally fine” writing but later claimed the market was saturated with the bestseller “The Grapes of Wrath,” the classic John Steinbeck novel on the same subject. In 2004, the University of Oklahoma Press published Sanora’s novel to strong appreciation and recognition that there were other incisive voices reporting on the Depression years and its social issues.

Sanora’s sister Dorothy was said to have offered literary criticism to her, and the former’s photographs, some 250 or so, provided their own exceptionally compelling reportage of Dust Bowl refugees.

Both sisters were among the young writers of their time affected by Depression conditions. As a website for the Babbs notes, “Adversity and a concern for social justice joined these young writers in an informal freemasonry of goodwill and progressive ideals that has seldom existed before or since in American literature.”

(For more information about Sanora and Dorothy Babb, visit http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/web/babb/gallery/)

In this America of today, not recovered from a recession of a few years back that almost became a depression, in a United States that must make choices that better humanity rather than harm it, choices over a dwindling middle class, immigration, health care, political direction and world responsibility, revisiting the social documentary work of Dorothea Lange through Neil Scott-Petrie’s added perspective and through the writings and photographs of the Babb sisters, makes us understand better the journey so far and reminds us of the utter responsibility we have for each other.

The writer is a retired newspaperman who can be reached at ahgunther@yahoo.com This essay may be reproduced.