By Arthur H. Gunther III

Decades ago, Rockland County, N.Y., faced an interracial situation that I covered as a Journal-News photographer. I offer my account and image of that July 4, 1966, event in Suffern to report on the non-violent protest and how in that situation the commonsense response from participants, the police and our volunteer fire departments unfolded. This was a day that led to great change and one which advanced race relations in the county.

When July 4, 1966, arrived, I was nearly 24, a Journal-News photog on the job for seven months, having been promoted from copyboy/engraver. I worked the Monday shift, which including day and night assignments. That Monday was a holiday, so I had those celebrations to handle, too. I was the only one of four J-N lensmen on the street that day.

The NAACP, CORE and others had joined the growing national conversation over civil rights, and the country, as well as Rockland, were halfway between the famous landmark 1964 Voting Rights Act and the 1967 Newark (and Nyack) riots.

Bill Scott, an African American and Rockland Congress of Racial Equality leader, who once ran for county sheriff, was a key spokesman in trying to integrate blacks into housing, jobs and the fire departments.

In newspapers like The Journal-News, police blotter items for such things as small street arrests always noted “negroes,” though the language would quickly change.

Rockland, which was becoming an ever-larger New York City suburb, included leaders and group spokespeople who saw opportunity to enlighten society and integrate, although prejudice surely continued.

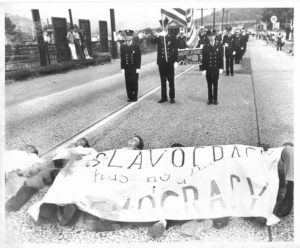

By July 4, 1966, tensions were heightened in fire department integration in Rockland, and a Dr. Martin Luther King-type protest — non-violent — was planned for the annual county fire parade route in Suffern. A group of six young men chained themselves together and by signal lay down on Orange Avenue, blocking the route.

I was there covering for newspaper as photog, Ann Crawford as reporter. Also there was the Bergen Evening Record, whose photos printed July 5 showed me taking photos.

I had expected this demonstration, and so, though my heart was beating fast, I checked my old-fashioned 35mm and medium-format cameras for proper exposure, etc. (nothing automatic then), so that I would not lose the shots. The demonstrators did what was planned, very calmly, singing, carrying a banner, and they lay down on Orange with the banner covering them. I was facing north on Orange, just in front of the protesters, who were blocking the Hillcrest Fire Department contingent. I snapped away, and then, quickly, Suffern police and, I believe, a county Sheriff’s Department officer, came over to pull the demonstrators, including Scott, away from the line of march and to make arrests. They were charged with disorderly conduct and released without bail.

I will tell you that the officers never interfered with my work of reporting the facts photographically. They also were polite to the demonstrators. I saw no batons used, no guns drawn, no tough-handling of the protesters, who in Dr. King fashion, had gone limp.

(A July 5 article in the New York Times reported that some of the estimated 3,000 parade watchers shouted that the six and about 29 other demonstrators should be doused with firehoses.)

I took my shots and some others of the parade itself, as that was the initial assignment, and went off to other assignments that day.

When the parade demonstration photographs were published July 5, The Journal-News was strongly criticized for showing the chained men lying in the street and not concentrating on the county fire parade.

After 1966, the fire departments began to accept African Americans beyond the four individuals already serving among Rockland’s 3,000 volunteers, and the county morphed into a veritable league of nations, so close it is to the Port of New York.

July 4, 1966, was perhaps not a turning point in race relations for Rockland, but it put the county on the road toward that, a route still to be trod by all, of course. It was also a day when the free speech of six peaceable demonstrators was recognized while the resulting police action and legal process took place in a peaceful, common-sense way.

The writer is a retired newspaperman. ahgunther@yahoo.com